Everyone Had a Story: The Haymarket Affair

May 9, 2023

In the United States,. Labor Day is celebrated on the first Sunday of September. Around the world, the plight of the working class is celebrated on the first of May. Ironically, May 1st’s association to labor movements around the world has its roots in America and the persecution of eight Chicago citizens. When these eight are not outright ignored or forgotten, they are demonized as radicals, terrorists, and monsters. These men are of course, the Eight labor activists tried for the Haymarket bombing.

One of the individuals executed was Albert Parsons. Parsons, the only of the accused born in the U.S. was born in 1848 in Alabama. Parsons and his family moved to Texas early in his youth.

However, when his then home state of Texas seceded from the union, Parsons’ would enlist in the Confederate army at the age of thirteen. After the war, Parson went to college, while also working in the printing and news trade. Parson’s writing at the time was very controversial, as he supported the reconstruction era measures to support the recently freed slaves of the south. In Parson’s own words, “lately enfranchised slaves over a large section of our country came to know and idolize me as their friend and defender, while on the other hand I was regarded as a political heretic and traitor by many of my former associates”.

Parsons found himself in further hot water when he married Lucy Gonzales-Parsons, a mixed race woman in 1872.

Both Albert and Lucy Parsons would move to Chicago together in 1874. They would fall into politics together, getting involved in Chicago’s growing labor movement.

“So they moved to Chicago when they were organizers at heart, you know, and the more he became involved in politics, the more radical he became,” said Larry Spivack, the President of the Chicago Labor Society. “This was a period where smart people, working people, could see the inequality. With Parsons being a writer and his wife having organizing instincts, they became union organizers and when they came to Chicago. For instance, several corporations stole the aid money that was supposed to go as relief from the Chicago Fire of 1871 and was used as interest free loans,” continued Spivack.

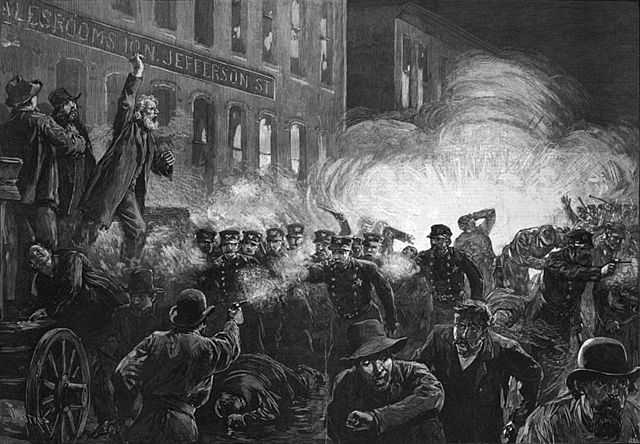

The Parson’s involvement continued into the May First Demonstrations of 1886. Both of them gave speeches arguing for the importance of the eight hour workday. When those gathered to hear them and other labor leaders talk were fired on by police, they retreated into hiding for three days. On May Fourth, Albert Parsons gave a speech to a rally of those showing their support for those injured by the police in Haymarket square, when tragedy would strike.

Shortly after Parson’s speech, a bomb was thrown into the crowd by a still unknown perpetrator. Eight would be killed. When the bomb went off, Parsons was not at the scene of the crime. Rather, he was drinking with fellow labor organizers. It was immediately clear that Albert was in hot water with the police. “When the bomb went off, people came and said ‘Albert, you’re the one that’s going to be blamed for this,’” said Spivack.

In the aftermath of the explosion, Chicago city officials and government rushed to find men to pin the blame on, and as the people of Chicago feared, Parsons was tied to the bombing on grounds that were tenuous at best. Parsons initially fled to Wisconsin but he “believed that the evidence against them all was weak, subsequently voluntarily turned himself in, in solidarity with the accused” according to Micheal Schaak, a police officer and chief investigator on the Haymarket bombing case.

The eight men were to be tried for conspiracy, as well as the murder of the officer killed in the blast. The evidence brought forward by the police and the defendants made it clear Parsons, and the others on trial, could not have possibly been implicated in the bombing. However, the prosecution wanted blood.

Chief prosecutor Julius Grinell realized the jury would not convict, due to the lack of evidence tying the men to the crime. Instead, he appealed to the fears of the crowd. “He didn’t have evidence to convict that there was no hard evidence. I mean, you know, most of the guys weren’t even present when the bomb was thrown. And so what he finally said was, he turned to the jury, and he said to the jury, ‘These eight men are no more guilty than the rest of you, but convict them for their ideas to keep our society safe’.” said Spivack. Ultimately, seven of the eight would be sentenced to death, Parsons among them.

Parsons would be hanged on November 11th, 1887. His last words were cut short when the signal to cut the trapdoor from beneath him was given while he was still speaking.

While Albert Parsons life as an activist ended early, Lucy Gonzales-Parsons would carry on their legacy. She would help sign the charter founding the Industrial Workers of the World, or IWW, in 1905. Gonzalez-Parsons would die in 1942, at the age of 91. She is buried alongside her husband and the others executed in 1887 at Forest Park Cemetery, in Forest Park Illinois.